September 16, 2013, marked the one-year anniversary of the implementation of the America Invents Act, and with it, the introduction of an important tool for challenging the validity of an issued patent at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office – Inter Partes Review (IPR). IPR has replaced inter partes reexaminations. In contrast, inter partes reexaminations were applicable only to patents issued from an original application filed on or after November 29, 1999; IPR is available for all patents.

The IPR procedure has altered the dynamics of patent litigation by adding a trial-like invalidity proceeding before the Patent and Trial Appeal Board (PTAB). The proceeding is designed to be simple, streamlined, on a controlled timeline, and is intended to serve as an alternative to patent litigation on questioning a patent’s validity.

What is Inter Partes Review?

Inter partes review is a proceeding that allows third parties to challenge validity on the basis of prior art patents and printed publications. As with other proceedings, an IPR proceeding is initiated at the PTAB by a petition made by any party other than the patent owner.

IPR can be commenced immediately following issuance (or reissuance) of patents examined under the first-to-invent rules (i.e., patents filed prior to March 16, 2013). But for patents examined under the AIA first-to-file rules (i.e., patents filed on or after March 16, 2013), IPR can be initiated after the nine-month window of eligibility for post-grant review. That is, post-grant review is a mechanism for challenging the validity of a newly-issued patent during the nine-month window immediately following its issuance. Inter partes review is the tool for contesting validity after that nine-month window.

Most notably, IPR is also subject to another limitation regarding co-pending litigation involving the patent at issue: The proceeding is only available during the first year after a party is served with a patent infringement complaint. A party is also estopped from filing for IPR if the party is already challenging validity of that patent in a filed civil action. Thus, the petition must be filed before a party seeks a declaratory judgment challenging the validity of a claim in the patent.

The IPR proceedings are conducted by a panel of three administrative law judges at the PTAB. These judges render a decision on petitions submitted. The decision is based on a petitioner’s reasonable likelihood of success on at least one claim. Because the petitioner must present its case at the onset, most petitions are supported by evidence from an expert witness. The PTAB applies the “broadest reasonable construction in light of the specification of the patent in which it appears,” and there is no presumption of validity. A patent owner has the opportunity to move to amend claims in a limited manner in an IPR. Doing so, however, may create intervening rights for third parties.

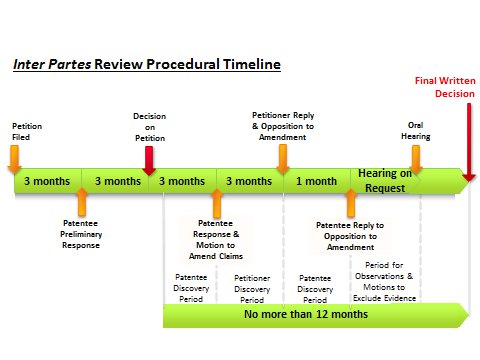

Once a petition is granted, the proceeding for an IPR is analogous to a shortened litigation. The grant will include a scheduling order setting the timeline for the trial, including the final written decision of the Board. Statutorily, the entire procedure must be completed within 12 months of the grant of the petition. Extensions of up to six additional months are allowed for good cause.

Invalidity need only be proven by a preponderance of the evidence, a lower standard than the federal court “clear and convincing” standard. However, discovery in PTAB proceedings is much more limited than in federal court patent litigation. Routine discovery in PTAB proceedings includes: (1) any exhibit cited in a paper or in testimony; (2) cross examination of any declarant; and (3) non-cumulative information that is inconsistent with a position advanced by a party. Additional discovery may be allowed if “in the interests of justice.” Direct testimony is submitted by affidavit, while all other testimony must be in the form of deposition transcripts with all objections made at the time of the deposition.

If the PTAB issues a final written decision upholding some or all of the challenged patent claims, the petitioner and its privies are estopped from raising the same arguments in a later district court proceeding against the patentee. The petitioner is also estopped from raising in later proceedings any arguments they reasonably could have made in IPR. Unlike inter partes reexamination where estoppel attaches after all appeal rights, including appeals to the Federal Circuit, have been exhausted, IPR estoppel attaches once the PTAB issues a final written decision. Accordingly, if the parties settle before a final written decision, no such estoppel exists. A party that is dissatisfied with the final written decision of the PTAB may appeal to the decision to the Federal Circuit.

Inter Partes Review in its first year

Over the past year, the PTAB received over 482 petitions for IPR with a total of 178 decisions rendered on whether to grant IPR. Out of 155 of those decisions, the Board instituted a proceeding; however, that number has been decreasing. Six months after its implementation, 96 percent of all IPR petitions were granted. That percentage has dropped 9 percent over the last six months most likely due to the increased number of petitions. Notably, petitions were granted for all of the challenged claims for 83 percent of petitions. This statistic is consistent with the percentage of requests for inter partes reexaminations that were granted each year. Unlike inter partes reexaminations, however, the PTAB often agrees to proceed on fewer grounds of rejection than were petitioned.

While IPR has had petitions for a wide range of technologies, most petitions filed over the past year were from the software, e-commerce and electrical fields. This is likely because these types of patents generate the highest amounts in damages at trial and are more closely tied to non-practicing entities. Moreover, this statistic is consistent with inter partes reexamination.

More than 60 percent of IPR requests in the first six months were connected to patents already being litigated; more than half of those litigations were stayed by the district courts pending IPR. Recent trends, however, have shown some courts are waiting to stay the case until the IPR is indeed granted. In any event, it is expected that most courts will continue to stay litigation if the petition is granted for review on all claims. More statistics show that petitioners often file multiple requests for IPR proceedings. Many times, multiple petitions are filed on the same patent by the same petitioner, a strategy likely compelled by the page limits on IPR requests..

In the sixteen months since IPR implementation, the PTAB has issued only one final written decision On November 13, 2013, the Board in Garmin v. Cuozzo (IPR2012-00001) ruled in favor of the petitioner, canceling all three patent claims at issue.. A review of the decision indicates the PTAB is willing to find obviousness based on a combination of as many four prior art references – a number which is rare in federal court patent litigation. The Board also provided a highly detailed analysis of claim construction as this analysis was critical not only for the Board’s invalidity determination, but also for the Board’s denial of the patentee’s motion to amend its claims based on this construction. While this first written opinion provides much insight into the Board’s process for evaluating evidence on invalidity, claim construction, and amended claims, no trends can be gleaned from this single decision. However, Garmin v. Cuozzo undoubtedly highlights how valuable IPR is as a defensive tool for those seeking to defeat meritless infringement claims.