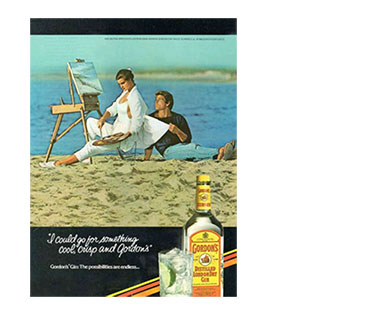

On December 15, 2015, Jeff Koons, an iconic U.S. pop artist, was presented with an all-too-familiar allegation — that his art infringed the copyright of another. See Mitchel Gray v. Jeff Koons et al., 1:15-CV-09727-SAS. Mitchel Gray, a commercial photographer, claims that Koons unlawfully reproduced his photograph (which had been utilized in a 1986 Gordon’s gin advertisement, as shown below) “nearly unchanged and in its entirety.”

Koons, whose work has been known to fetch as much as $58.4 million, is no stranger to allegations that his art infringes others’ copyrights. He often uses pre-existing images to comment on contemporary culture, and that kind of work carries inherent infringement risks.

Koons often relies heavily on the fair use defense. Initial courts found his argument unavailing, however. Indeed, the fair use doctrine didn’t work in his first case, which reached the Second Circuit, the nation’s preeminent copyright court. The 1992 case, Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992) affirmed that Koons infringed the plaintiff’s photograph by usurping nearly the entire essence of the plaintiff’s work — much more than would have been necessary even if the court were to accept Koon’s argument that the sculpture constituted a parody of the original work.

However, in a 2005 case involving the copyright of a photograph used in shoe advertisement, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York focused heavily on the “transformative” nature of Koons’ work and agreed that this art fell within the fair use exception. In Blanch v. Koons, 396 F. Supp. 2d 476 (S.D.N.Y. 2005), the court stressed that “to the extent that the secondary use adds something new, with a further purpose of different character…the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered.”

The court noted that Koon’s art, copied only the models’ legs, feet, and Gucci sandals from the plaintiff’s original photograph. Moreover, in Koons’ piece, the legs were removed from their original context, totally inverted, added to other contrasting images of legs, and floated playfully above a liberating landscape of grass, a waterfall, and sky.

As a result, the court agreed that Koons had transformed the meaning of the legs (as they appeared in the original photograph) into the overall message of how commercial images intersect in our consumer culture and simultaneously promote appetites like sex, and confine other desires, like playfulness. Therefore, the court held that Koons’ painting did not merely supersede or appropriate the objective of the original photograph, but instead used it as raw material in a novel context to create new information, new aesthetics, and new insights.

These and other Koons cases have set the stage for the artist’s latest copyright dispute involving the Gordon’s Gin advertisement. The court will be forced to ask whether Koons made fair use of another’s copyrighted work or whether he has gone too far. Has he transformed the original work into something new or merely appropriated the work in its entirety? Does the Gin Artwork fall closer to the Rogers v. Koons spectrum — thus finding that fair use is not an appropriate defense? Or will the Southern District of New York find that Koons’ commentary on contemporary culture has added value beyond that of the original work?

Like the cartoon dog Odie, portrayed in another of his works, Koons will be eagerly awaiting the court’s decision.

Justin Mulligan is an associate in Thompson Coburn’s Intellectual Property group. He can be reached at (314) 552-6227 or jmulligan@thompsoncoburn.com.