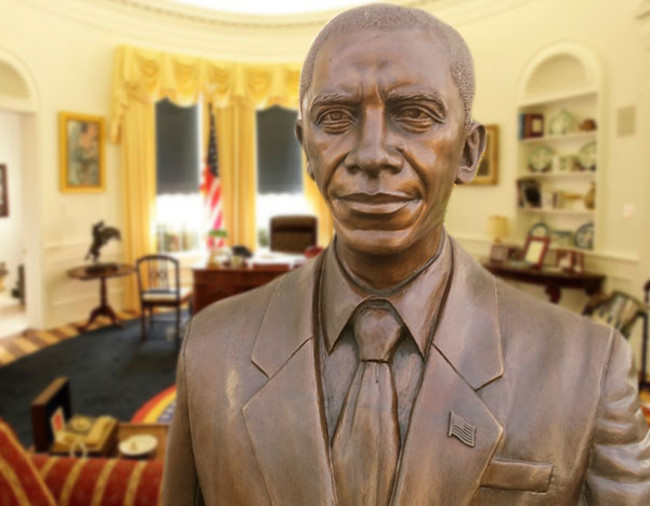

Credit: Original photo by Paul Sableman. Deceptive alterations by Unknown and minor cropping by In Focus.

As Creative Commons licenses are more widely used, questions are developing about how to use them, and how they apply in particular situations. This column addresses some of these emerging CC interpretations.

Can you take a Creative Commons photo and alter it, making a false or misleading final product?

This question was raised, for example, when a photo that my son, Paul Sableman, took in Puerto Rico, was photoshopped onto a fake Oval Office background, and used in a tweet that falsely claimed President Obama had installed a statute of himself in the White House.

If an author allows derivative works (adaptations) to be made, the Creative Commons license doesn’t contain any prohibition against making false, misleading or deceptive images, so even deceptive and misleading works are presumably within the derivative-works license grant.

In these cases, however, the creator of the deceptive work is likely to run afoul of the most basic Creative Commons requirement, of attribution. If, as is most likely, the creator of the deceptive work doesn’t include attribution to the original photographer, he has violated a key Creative Commons requirement. And if he does attribute the doctored photo to the original photographer, that attribution is likely to falsely portray the original photographer, setting up possible claims for fraud, libel, or false light.

There may be a middle course – an attribution along the lines, “Original photo by Mary Jones. Deceptive alterations by John Smith.” But that kind of truthful attribution doesn’t seem too likely to occur in these situations.

Can someone make money off of a non-commercial Creative Commons license?

Yes, according to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Great Minds v. FedEx Office. It was permissible for FedEx Office to make money on the copies of Creative Commons works it made on behalf of its customer. Since the customer, a nonprofit organization that produces educational materials used by school districts, had a non-commercial use Creative Commons license, it was within its right to employ FedEx Office to make copies of the work, even if FedEx Office’s normal copying charges carried a profit for FedEx Office.

The court applied standard principles of agency law, including the principle that a licensee of intellectual property is permitted to contract with others to supply him with copies that he is entitled to make (or, in the case of patents, products he is entitled to make). Because Creative Commons licenses don’t prohibit or restrict such customary delegations, the CC licensee can use third parties and pay them, even if they make a profit. The “non-commercial use” restriction on the CC license applies to the licensee itself; that is, its use must be non-commercial.

The court held: “As the school districts are the entities exercising the rights granted by the License, it is irrelevant that FedEx may have benefited by having been hired by them to act, viz. make copies, in their stead. *** In sum, the unambiguous terms of License permit FedEx to copy the Materials on behalf of a school district exercising rights under the License and charge that district for that copying at a rate more than FedEx’s cost, in the absence of any claim that the school district is using the Materials for other than a ‘non-Commercial purpose.’”

Mark Sableman is a partner in Thompson Coburn's Intellectual Property group.