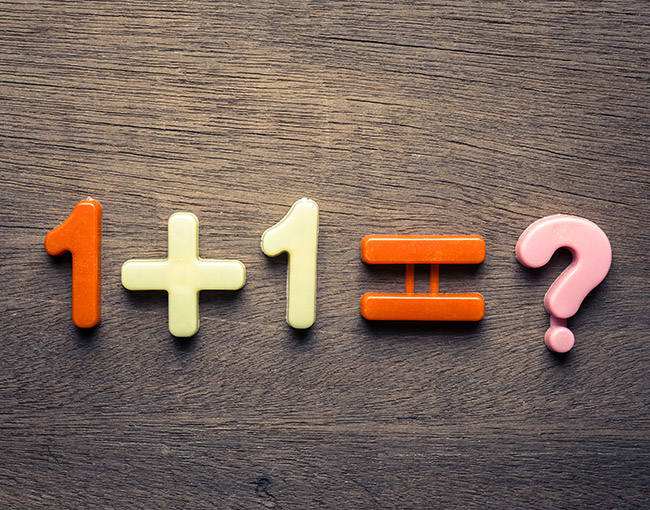

Everyone — including lawyers and judges — likes simple legal rules. And the copyright act seems to provide one, with its fair use provision listing four factors. So determining fair use should be as simple as adding up the scores on these four factors, right?

Wrong. Really, really wrong. Fair use requires complex and nuanced judgments, not simplistic arithmetic. Any arithmetical method for determining fair use will almost always be erroneous.

First, there aren’t just four factors. Section 107 of the Copyright Act, on fair use, calls for weighing all considerations, which “shall include” the four factors it expressly lists. In various cases, courts have considered other factors beyond the ones listed, including the public interest, customs and traditions, and the defendant’s good faith.

Second, the four listed factors aren’t co-equal. In recent years courts have come to discount or ignore the second factor (the nature of the work) since most litigated copyrighted materials are creative works. And based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s focus on whether a defendant’s work is “transformative,” the first factor (the purpose and character of the use) and fourth factor (effect on the market) which give rise to that issue, often weigh most heavily. When a trial court in Georgia treated all four factors equally, the Eleventh Circuit reversed that ruling as using plainly erroneous reasoning.

Third, fair use requires a holistic analysis, and should never be mechanized or put into a formula. On remand from the Eleventh Circuit ruling about the error of treating the four factors equally, the district court developed a new formula with tailored weights for each statutory factor — first factor 25%; second, 5%, third, 30%, and fourth, 40%. But the trial court’s use of that formula was also reversed, for failing “to give each excerpt the holistic review the [Copyright] Act demands.”

The statutory fair use factors are simply a non-exhaustive checklist of things to consider, not a formula for decision. Fair use analysis must be tailored to all the circumstances of each case, and informed by the many precedents in the area. One can be cynical and call Section 107 the “Copyright Lawyers’ Full Employment Act.” But the holistic approach is necessary for fairness. It calls for attorneys and judges to use a common law, case-by-case, equitable approach when evaluating cases or issuing a decision — and that is an important calling in an arena where circumstances and context matter a lot.

Mark Sableman is a partner in Thompson Coburn’s Intellectual Property group.