The new technology of facial recognition is starting with a smile. But as it develops, people may begin picturing it with a frown, or maybe a furrowed brow.

Currently facial recognition is primarily being used now to identify friends in social media, and to manage personal photographs. Finding friends and organizing family photos — these are truly useful, wholesome, and laudable results.

But that is just the beginning, a Government Accountability Office report warns. Like other new digital technologies, facial recognition will soon develop robust commercial applications. And the privacy implications of those applications could raise serious concerns, and difficult policy choices.

Even existing uses may raise some eyebrows. Did you know, for example, that existing-technology digital signs scan your face to determine what message to display just for you? These signs, usually on in-store televisions or kiosks, first use cameras to scan the viewer (you), and then change their message display, directing it to someone of your age and gender. Next step: “In the future, such signs may be used to identify customers by name and target advertising to them based on past purchases or other personal information about them.”

The GAO study builds on both a 2012 FTC staff report, and the information contributed by participants in the "multi-stakeholder process" that the Obama administration has been quarterbacking for the last few years in an attempt to have industries develop fair information practices that would in turn become legally enforceable by the FTC. The facial recognition multi-stakeholder process, begun in 2013, is still proceeding, although the recent withdrawal from the process of a number of public interest groups may impede its effectiveness.

To the average person, facial recognition seems like an amazing technology. But the report notes that it is just one of many kinds of emerging biometric recognition systems – others are based on fingerprints, hands, retinas, irises, voice, and even gait.

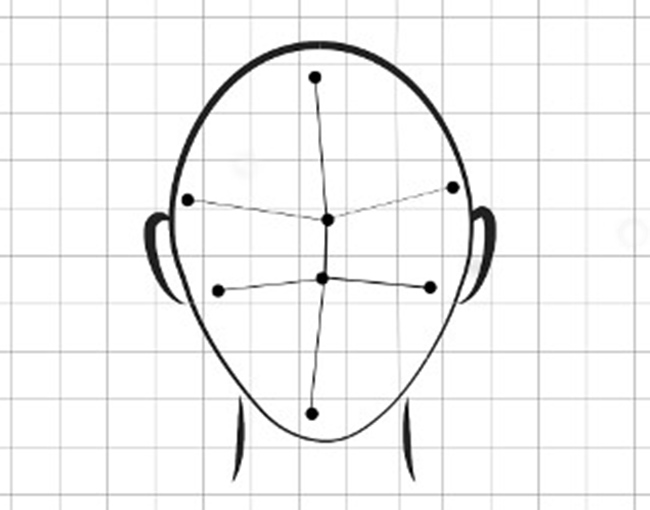

Facial recognition technologies work through a four-step process: (1) image capture, (2) an algorithm creating a “faceprint,” (3) a database of stored images, and (4) an algorithm to compare the captured image to ones in the database.

For those who fear Big Brother, the report carries both good news and bad news. Different facial recognition systems use different methods of creating faceprints, so cross-system comparisons aren’t currently feasible. But as for the databases – well, users of social media are uploading and labeling billions of photos, “creating a vast repository of facial images that are often limned to names or other personal information.”

We know some of the current uses of facial recognition, but some current practices and most future practices can only be guessed. Two well-established uses, “finding friends” and “organizing photos” are relatively benign. Also, the technology is being used in some commercial security systems, such as ones at banks, casinos, and retail operations, but GAO admits that it doesn’t know the full extent of those uses. GAO expects the next likely applications will relate to securing access to computers, phones and gaming systems in lieu of a password.

More transformative uses may occur in applications aiding customer service and marketing. That seems to be the area where privacy views conflict most, as industry and consumer groups put forth diametrically opposite views. The consumer groups, generally, argued that consumers should control how their facial features are used, should be protected for theft or misuse of that data, and that discriminatory use of the data should be forbidden. Industry trade associations, in general argued that people can’t expect anonymity, that surveillance is a part of our daily lives, and that consumers often willingly give up some privacy in return for technological benefits. Most strikingly, the two sides clashed on any requirement for notifying consumers or obtaining their consent.

This policy debate is just beginning, and it promises to be a big one. If use of facial recognition becomes widespread, the report states, “it could give businesses or individuals the ability to identify almost anyone in public without their knowledge or consent, and to track people’s locations, movements, and companions.” Additionally, the report notes, concerns have been raised that “information collected or associated with facial recognition technology could be used, shared, or sold in ways that consumers do not understand, anticipate, or consent to.”

In our common law system, court decisions more often lag than anticipate new developments. And our basic privacy working principles are somewhat general, like (1) activity in public view is generally not private, and (2) individuals are entitled to reasonable expectations of privacy. We currently recognize a right to be free from “intrusion” upon one’s privacy, for example, but those principles developed slowly out of old-fashioned trespass law and were slow to adapt even to relatively old technologies like telephoto lenses and electronic eavesdropping bugs.

Facial recognition technology will require courts and policymakers to take a brand new look at the public or private nature of the smiles and frowns of our daily lives.

Mark Sableman is a partner in Thompson Coburn’s Intellectual Property group. He is the editorial director of Internet Law Twists & Turns. You can find Mark on Twitter, and reach him at (314) 552-6103 or msableman@thompsoncoburn.com.